The first Saturday in June is “National Trails Day,” established as a day of public service where individuals and organizations come together to advocate, maintain, and clean up public trails and lands. There were several gatherings near me this year; I chose to join members of the organization E Mau Nā Ala Hele for their annual membership meeting followed by a short hike.

Established in 1979 here on Hawaiʻi Island, the goal of this non-profit is “To preserve and protect the ancient and historic trails of Hawaiʻi including their natural and cultural surroundings.” Over the decades, they have been instrumental in seeking the establishment of the State of Hawaiʻi trail system as well as recognition of the Ala Kahakai as a federally designated trail.

Members and friends of E Mau Nā Ala Hele gather on National Trails Day 2022. Thatʻs me on the right in bright blue tights, chartreuse shoes and a Hawaiʻi Life t-shirt.

Universal Hikerʻs Code – What is responsible use of public trails anywhere?

Of course the mission of E Mau Na Ala Hele is aligned with our efforts in Hawaiʻi Lifeʻs Conservation and Legacy Lands initiative. On a personal level, I have been an avid hiker for four decades. I have summited 21 of Coloradoʻs “Fourteeners.” I have a knee that still complains from hours of jogging downhill the day I got sent down the wrong trail by my guide. I was lost alone until after sunset on one of many hikes in the Swiss Alps, arriving back at the hotel to find the rest of the group calmly enjoying a fondue dinner, unconcerned since the hiking company owner assured them I was completely competent in the mountains and if I didnʻt show up they would send out a search team in the morning!

Because I find so much solace and wonder in the natural world, I am also dismayed at how often I now find trails – both public and “secret” — overrun with visitors more intent on taking selfies in dramatic surroundings or recording their vacation via hashtag than in communing with Nature. Those responsible for stewarding trails, in Hawaiʻi and elsewhere, find themselves dealing with overuse and irresponsible use, entitled attitudes, mounds of rubbish, and outright trespass.

The American Hiking Societyʻs website encourages visitors to take a pledge to commit to leave the trail and the outdoor community better than you found it. For sure if you use a trail, you have to take out everything you bring in, and while you are at it pick up someone elseʻs litter. Recently at Pololu Lookout, one of the stewards reported on a group of young people visiting from Colorado who brought out 6 bags of trash. How beautiful would our trails and parks be if we all saw ourselves as stewards!

Sometimes committing for trails to be better than they are today means putting the trail and community ahead of your own desires — including choosing not to hike when it looks crowded or conditions could be unsafe…and respecting closures for maintenance and restoration of habitat.

And seriously my dear readers, when it comes to hiking and access NO MEANS NO!

When I see multiple signs I am pretty sure it is because one was not doing the job. That pretty path is not a public trail even if you saw it on IG.

This is particularly true when you see a sign on the boundary of a trail…or on a path leading off the established trail… that says “No Trespassing” or “Kapu” or “Private Property.” Think of it like this. While everyone in your neighborhood is welcome on the sidewalks, you donʻt have the right to use your neighborʻs front lawn just because it is adjacent to the sidewalk!

Responsible Use of Trails in Hawaiʻi – A Conservation and Legacy Lands Concern

In 2018, the County of Hawai’i and the Island of Hawai’i Visitors Bureau launched a “pono pledge” campaign. While targeted at the visitor industry, the Pledge makes just as much sense for those of us who are resident here when we visit undeveloped places including our beaches, mountains and parks.

The Pono Pledge begins “I will mindfully seek wonder, but not wander where I do not belong.” Sometimes you will see hand made signs these days proclaiming “Know your Place” — a phrase that intentionally carries multiple meanings, including if you donʻt already know this place, “know your place” in the sense of approaching it with humility.

In a conversation last weekend, one of the other hikers described a place known as sacred to Hawaiians by saying “there is nothing there.” My response is that if you donʻt know the history and stories of that place — and if you are not a specialist in geology, archeology, and botany — how can you make a grounded assessment that “there is nothing there”?

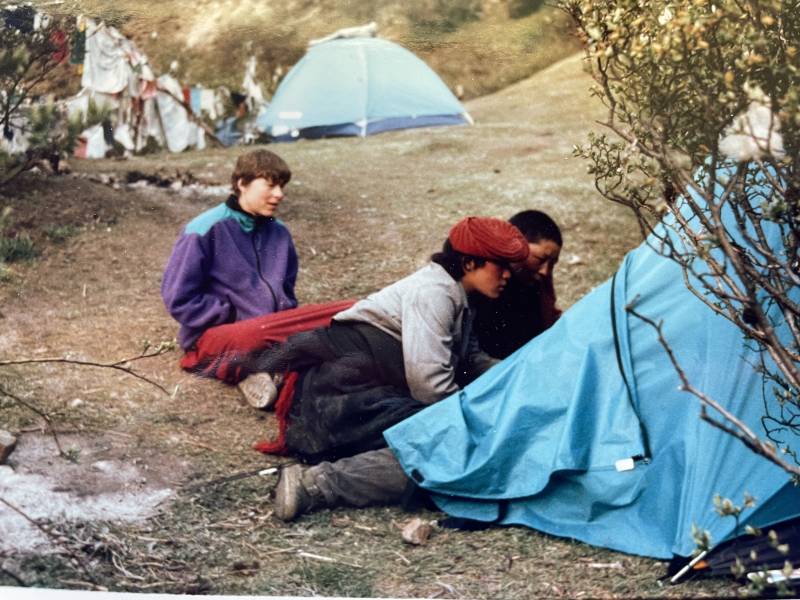

Tibet 1992 – me watching young Tibetans inspect the wonders of my backpacking tent and the sleeping bags inside.

I learned this lesson on a three-week trip to the Himalayas thirty years ago last month. For nine days three of us visitors and our driver, cook and interpreter were camped at a place in Tibet called Shoto Terdrom, at an altitude of 16,000ʻ above sea level. One day I was invited to walk a circumambulation of the valley, along a well-trod path in the vicinity of the ani gompa or convent, by two young Buddhist nuns and two equally young men visiting from Kham. I had hiked this path before not seeing there was “anything there” but rock and scrub. This time my volunteer guides pantomimed for me the ritual motions of respect and showed me what was hidden.

From my journal: “We donʻt take the gentle lower path, but clamber up the rock over the river. This is a blessing, for the sacred images lie above. First we look up a narrow opening at a very dark, well-defined image of Guru Rimpoche, and touch our head to the rock. We rub our palms over a footprint. We prostrate three times in front of a cave. We climb up the rock chimney as Iʻd seen others do from my meditation perch. I hadnʻt seen what was beyond: a narrow, claustrophobic channel through which we were expected to wedge ourselves sideways, then eight feet into it hoist ourselves vertically through an opening of no greater width. The young men had to remove their head wraps and belts to make themselves thin enough. The ani held these and the jacket Iʻd tied around my waist, climbing over the top to meet us. We rested, panting, on the other side. They gave me a thumbs up sign, laughingly saying ʻBuddhistʻ.”

I feel fortunate to have had these experiences. On this trip I was not in Tibet as a tourist seeking to check a box on my bucket list. I went in service, supporting an artistic project designed to listen deeply and promote harmony and healing for communities and the earth, drawing attention to and preserving special places around the globe.

So the next time you hike in Hawaiʻi, please join me in taking these two pledges. To leave our trails and special places better than we find them, and to respect Hawaiian places according to traditional principles of stewardship of Hawaiʻi.

E kū i ka pono ke kipa o Hawaiʻi.

Jann C Buckner

June 10, 2022

thank you for this article and it’s reminders

Beth Thoma Robinson, R(B)

June 10, 2022

> Jann, thank you for reading and commenting. Feel free to share it!